NFC Ticketing Stuck at the Station: Tech Challenges Contribute to Stall

NFC Times is Expanding Its Coverage

This story is a free sample of new premium content from NFC Times, the most authoritative source of news and analysis in the industry.

To view this sample story, click here:

Or download it as part of a free sample of the world’s first global PDF newsletter devoted to the business of NFC and related topics:

NFC Times: The Intelligence Report

Become a subscriber to NFC Times to receive future issues of the newsletter and exclusive online news and analysis:

Subscription Options

Five or six years ago, transit ticketing was predicted by many to become first big application service providers would launch when NFC rolled out commercially.

But today, even as NFC service begins to roll out–focused mainly on retail payments–prospects appear slim for any significant NFC transit ticketing projects to launch this year.

There might be a few adopters among transit officials, especially in Asia, where fare-collection schemes are more nimble and have moved into retail payments.

Transit fare-collection operators in South Korea and Japan, the latter using proprietary FeliCa technology, have launched large-scale projects.

In addition, there is some interest in Russia, China, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand and United Arab Emirates, where agencies plan local or regional mobile NFC ticketing launches.

But for the mass of transit authorities and operators, technical and, especially, business issues stand in the way.

Many of the transit companies see the value of moving to mobile NFC. But they don’t have the extra money to spend or a clear route to a timely return on investment.

“It’s expensive because it’s complicated,” acknowledged Steve Bryant, UK-based head of product, NFC transport and ticketing, at France Telecom-Orange Group, speaking at a recent conference. “It’s difficult to associate additional direct revenues when you migrate to mobile NFC. There are, however, savings. But the problem, again, the savings, if you’re doing a business case, do these savings realize in three years? Maybe not.”

That kind of ROI would be a tough sell to the CFOs of transit organizations, many of which are subsidized by the government and don’t have a lot to spend on innovation, he said.

Bryant has ideas for how transit authorities and operators could make the business case work–mainly by capitalizing on the location-based data transit operators could easily collect with the help of telcos and use to sell more of their own services, such as unfilled seats in first class, and those of merchants and other advertisers located near transit stations or stops.

Of course, mobile operators would want to be compensated in some way to help transit authorities or transit operators to offer NFC mobile ticketing.

But there are other challenges facing transit authorities and operators, which are considering launching mobile NFC ticketing, and some of these are purely technical.

While perhaps not as daunting as the business issues, the technical challenges are likely causing some transit agencies or operators of fare-collection systems to think twice about mobile NFC.

These problems, like the difficult business case can be overcome, say mobile NFC-ticketing backers. But it’s not going to happen overnight.

Waiting for Mifare

The technical challenges mainly center on the occasional problems for NFC phones in transmitting ticketing or account data to terminals at metro and train gates and onboard buses.

The antennas in NFC phones don’t always couple or connect with the antennas inside transit readers on the first tap.

There is also an issue of speed of transactions, which would mainly be of concern to large transit agencies that do not want to disrupt the flow of customers through their busy metro turnstiles or past their bus validators.

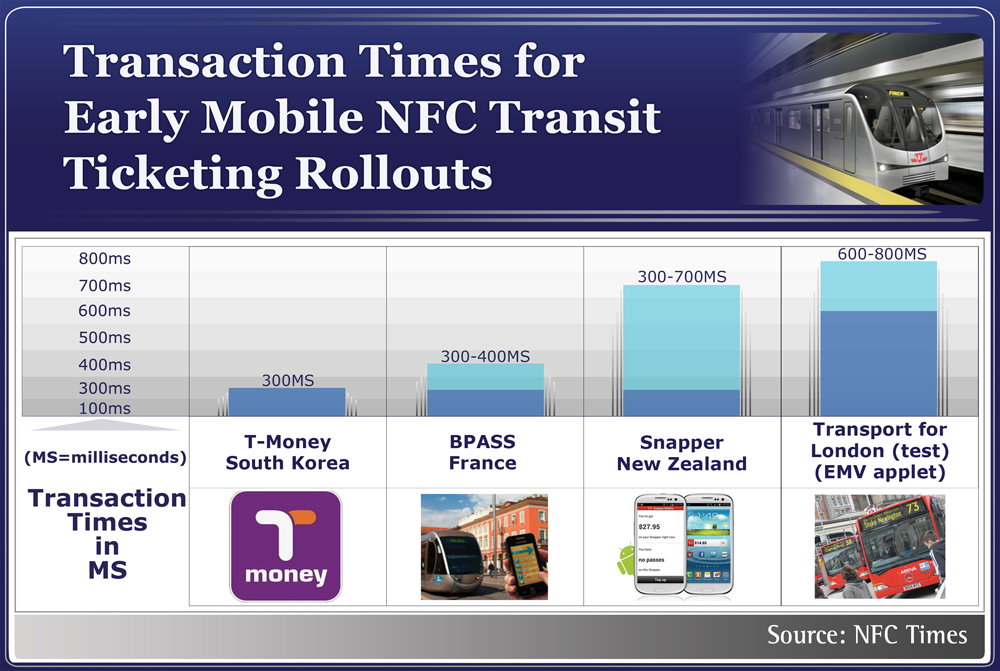

For example, operators of South Korea’s T-money fare-collection scheme said transactions were too slow until it optimized software on readers to bring times down below 300 milliseconds, on average.

For example, operators of South Korea’s T-money fare-collection scheme said transactions were too slow until it optimized software on readers to bring times down below 300 milliseconds, on average.

Transport for London said tests of EMV credit and debit applications on NFC phones came in at an unacceptably slow 600 to 800 milliseconds.

In addition, there have been problems implementing Mifare on SIM cards and other secure elements and in managing the applications over the air.

Mifare is the dominant contactless transit ticketing technology, used in roughly three-quarters of contactless transit fare-collection systems worldwide.

The latest specifications from vendors in the Mifare4Mobile industry group, which include Mifare owner NXP Semiconductors and key backer Gemalto, are designed to fix many of these problems. The industry group released delayed specifications in late March.

The Mifare4Mobile 2.0 specifications enable service providers to issue multiple Mifare card applications on a SIM or other NFC secure elements; to support a more secure version of Mifare, DESFire; to offer more interoperability among trusted service managers and secure-element providers; and to display Mifare-based content on handset screens in mobile wallets.

Some limitations remain. For example, it might be difficult for users to have multiple Mifare services running in their mobile wallets at the same time, such as a transit ticketing and stadium access control. The terminals might not know which Mifare card on the phone to address, though, if the services support DESFire, NXP says multiple services could be active.

Coupling Concerns

Mifare technology, which will soon mark its 20th anniversary, was designed for cards, so it remains to be seen how well the Mifare services can be managed on SIMs or embedded chips over the air. The Mifare services on the secure elements are called virtual cards, not applets.

Meanwhile, the legacy of contactless transit-ticketing terminals is also presenting problems for mobile NFC, especially for ensuring that the NFC antenna in the phone couples or communicates properly with the antenna in the reader at subway gates or bus validators.

Unlike standard contactless transit cards, which transit terminals were designed to read, the antennas in NFC phones are often smaller and situated in different locations depending on the make or model of phone.

This can cause problems for users, who often don’t know the location of the antenna on their phones, so they might have to tap the device more than once to transmit the data.

And unlike NFC payment at retail point-of-sale terminals, users don’t have as much time to reposition their phones on the terminal to make sure the two devices connect. Moreover, there is no global standards body that could enforce uniform specifications for terminals, as there is with EMVCo for contactless retail payment.

In any case, there is already a massive base of terminals deployed, and it will take time to for these to be changed under normal replacement cycles. According to NXP, there are 40 million acceptance points for Mifare, though not all of them are conventional contactless transit terminals.

“Coupling is still the biggest problem of (mobile) NFC,” Ahmad Saif, CTO of France-based Dejamobile, a developer of NFC-enabled applications and services, including transit ticketing, told NFC Times. “What’s important for the users is the ‘feeling time’ for the transaction, not the real time. (There is) no perfect reader for all devices.”

Study Demonstrates Problem

He said metal in the phones and even variations in the tiny distances between the coils of the NFC antennas in the phones can affect its ability to make a connection with the antenna of the transit reader in order for the card and reader to exchange ticketing data.

In a small study of NFC transit ticketing conducted at the end of last year, UK-based Fenbrook Consulting found that coupling was the biggest difficulty for users.

The consulting firm conducted the study with users of nearly 100 phones, all of them the NFC-enabled Samsung Tocco Lite, which stored a transit application complying with the UK’s ITSO standard on SIM cards issued by Orange UK. The users were asked to tap the phones on contactless readers onboard buses operated by Stagecoach group in the UK cities of Cambridge and Peterborough.

The consulting firm conducted the study with users of nearly 100 phones, all of them the NFC-enabled Samsung Tocco Lite, which stored a transit application complying with the UK’s ITSO standard on SIM cards issued by Orange UK. The users were asked to tap the phones on contactless readers onboard buses operated by Stagecoach group in the UK cities of Cambridge and Peterborough.

“How people present phone to reader on a bus with a card–it’s very hard to get it wrong,” Trevor Crotch-Harvey, director of Fenbrook and a specialist in contactless ticketing, told NFC Times. “But every NFC handset has implemented NFC in a different way. There’s nothing intuitive, if you’ve never done it before, about placing a phone on a reader and expecting to get a result.”

John Verity, chief advisor to UK-government backed ITSO Ltd., which manages the national standard for transit ticketing, agreed that coupling is a significant concern that the NFC industry must deal with. Verity is also working on a European standard for interoperable transit ticketing.

”There is this issue of coupling because the way the reader and phone interact is clearly very crucial,” he said.

Photos provided to NFC Times from T-money, the Korean transit fare-collection scheme considered the largest rollout of mobile NFC ticketing to date, demonstrates the problem. The photos show six NFC phones made by either Samsung Electronics or LG Electronics, and the antennas are in three different locations on the backs of the phones.

Three of the phones have the antenna in the upper third of the handsets, two are in the middle and one is located in the lower half of the device.

In addition, three of the antennas are rectangular with the long sides running horizontally across the upper end of the phone, while the other three devices have a square or near square antennas, tracing the dimension of the battery.

“Yes, the location and configuration issues are critical,” Young-Wook Park, CTO for Korea Smart Card Corp., which operates T-money, told NFC Times.

Speed an Issue for Large Transit Systems

He added that Korea Smart Card also faced a problem with slow transaction speeds when it put its Java-based application on NFC phones. That could disrupt the flow of customers passing through crowded gates and bus readers for transit operators accepting T-money in Seoul and surrounding areas. Korea Smart Card collects 1.5% of each transaction, so it has no interest in slowing them down when it introduced mobile fare collection.

“In Seoul case, we had the similar problem in the initiation period. However, we could solve this problem quickly by optimizing reader-side software.”

With that fix for the readers, he said the company was able to increase T-money transaction speeds to less than 300 milliseconds with the power of the phone on and slightly more with power off–well within the roughly half maximum transaction speed large transit agencies and fare-collection schemes say they can accept.

But even after the fixes, he added that some venders’ NFC SIM cards had some “serious defaults for (the) transportation environment.” He declined to name the vendors.

Transaction times vary for closed-loop transit schemes. And putting the application on SIM cards adds to the “overhead” for the transaction. Some experts blame those slower speeds on the larger operating system on NFC SIMs as compared with those for contactless cards or embedded chips. Others point to the physical connection between the SIM and NFC chips.

The operating system and applet–and efficiency of the transit application–varies according to the SIM vendor, noted Pierre Combelles, business lead for mobile commerce and NFC at the mobile operator trade group the GSMA.

“They (transit operators) have for a long time been cautious about mobile NFC because of this speed question,” he told NFC Times. “Before coming with definite conclusions with the speed question, the way the application has been implemented is absolutely key because it results in very different (transaction times).”

But the physical link between the NFC SIM card through the single-wire protocol connection to the NFC chip and antenna can add some milliseconds, as well, said Robert Meppelink, technical consultant at the Netherlands-based UL transaction security unit.

“Transaction speed depends on what kind of transaction you’re doing,” he told NFC Times. “The SIM card has to speak to the NFC antenna; that’s an extra step it has to take. For each command and response, you get a 5-millisecond surplus do to this extra layer.”

UL’s transaction security unit, which is a testing tool provider and consultant, did the tests on a Mifare card application running on standard SWP-SIM cards.

Closed-loop transit ticketing cards and applications on NFC phones can exchange perhaps 10 to as many as 50 commands and responses, he said, depending on the number of ticketing types, such as pay-as-you go or monthly passes, as well as discounts and other fare policies and ticketing rules.

He and other experts say the biggest factor in the time it takes for both mobile NFC and cards to complete a transaction is the number of back-and-fourth communication between the terminal and fare media.

For example, the Snapper contactless payment scheme in New Zealand, which has about 10,000 active users for its Touch2Pay mobile NFC ticketing service launched in May with telco 2degrees has seen transaction speeds of 300 and 700 milliseconds for NFC transactions on buses, Snapper CEO Miki Szikszai told NFC Times.

“The calculations on buses, for example, can be very complex as there are variables to consider–both for the bus–location, route and the customer-concession entitlement, previous activity (and) time of day and whether the customer is tagging on or tagging off,” he said.

He added that the transaction could be simpler, for example, if the customer is using a weekly or month pass product, in which where the reader is simply checking if the pass is valid for the ride.

Transport for London: Mobile NFC Not Ready

But bank issued EMV credit, debit or prepaid applications can be even more complex. Some large transit authorities are introducing open-loop collection of fares and the first among the major transit systems to do so is Transport for London.

The transit authority is also perhaps the most vocal critic of mobile NFC, especially transit applications implemented on SIM cards. The agency has said NFC can’t hit even the maximum 500 milliseconds it says it can live with to enable customers to flow through its Underground gates during peak hours.

In tests conducted by its consultant, Consult Hyperion, transaction times came back at 600 to 800 milliseconds with EMV credit or debit applications running on SIMs and other secure elements on a small number of phones.

“Obviously, what we would want to see is the sort the speeds we expect with contactless bank cards today,” said Peter Lewis, external initiatives manager for Transport for London, at a recent conference.

Handset makers, not Transport for London, wanted to do the mobile NFC tests, said a source. The transit authority is too busy with its continuing effort to move to open-loop fare collection from EMV contactless cards to worry about mobile NFC for now.

The authority launched the service on the 8,500 buses it oversees in London and plans to expand that to other modes of transport, including the Underground and to inaugurate its sophisticated back-office authorization system by the end of this year.

But even with EMV banking cards, a substantial number of transactions in tests were above 500 milliseconds, as terminals polled for both closed-loop Oyster and ITSO, as well as EMV and then the type of EMV card and then to follow the EMV protocols. Speed varied among card manufacturers with a small percentage even coming in above 900 milliseconds.

Closed-Loop Transit Speeds Fast Enough

Systems integrators are optimizing the reader software and applications to reduce the communication routines between cards or NFC phones and the terminals.

Mobile NFC backers say for most closed-loop transit applications, mobile NFC is fast enough already–as long as phones and readers couple properly, as demonstrated by the early rollouts, such as T-money in South Korea, Snapper in New Zealand and the BPass mobile ticketing service from Veolia Transdev in Nice, France.

And FeliCa-based Mobile Suica transactions in Japan, optimized on embedded chips, are believed to come in well below 300 milliseconds. East Japan Railway co., the owner of the Suica fare-collection scheme, took more than two years of testing and tweaking to ensure the speed of mobile-FeliCa phones were speedy enough for its super-fast ticketing gates.

In the case of Veolia, which operates buses and trams in Nice, transaction speeds are 300 milliseconds, according to Veolia’s Florent Cetier. He added that transactions are faster on contactless cards as compared with the same Calypso-based card application on SIM cards. A source at Orange France said transaction times for BPass in Nice were running about 400 milliseconds, still well within the requirements Veolia has for speed.

ITSO’s Verity also said tests show 300-millisecond transaction times are possible with the UK standard on NFC phones.

“We are firmly of the opinion that NFC is coming and is an acceptable form factor and will meet the standard for speed, as well as other standards that we are setting for other transport applications.”

That may be the case, but until vendors iron out the technical issues and, more importantly, provide a more convincing business case for often cash-strapped transit authorities, mobile NFC ticketing seems likely to continue to fail to live up to its earlier promise. NT